This post is based on a talk I gave at the 2023 edition of the Pint of Science festival in Edinburgh. Some of the issues I discuss here I explore in greater detail in my article ‘Scientific Values and the Value of Science’ published in Science & Education (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-023-00461-4).

What is the value of science?

Science – as a system of knowledge and as an activity – is valuable for many reasons but I’ll focus on what I believe are three main ones. Firstly, science is valuable because it enables a better understanding of the natural world. It’s an activity that for thousands of years has given humanity pleasure – ‘the pleasure of finding things out’ (Feynman, [1955], 1999).

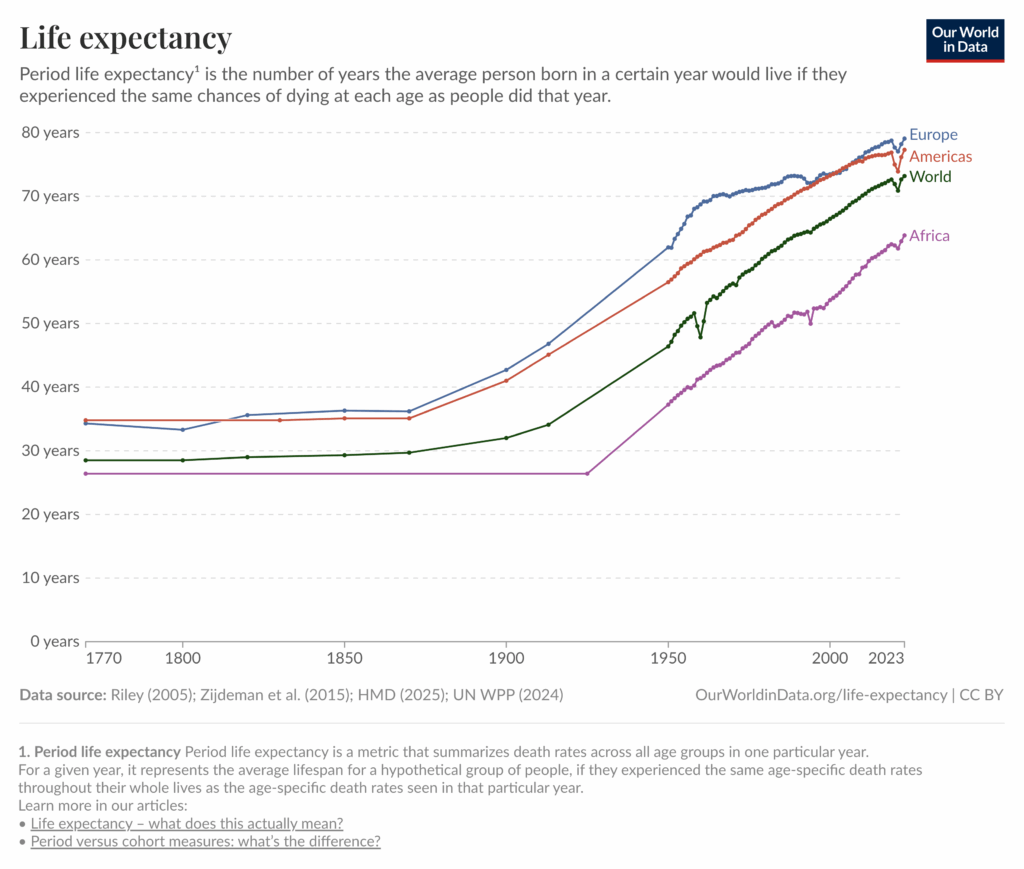

Science has also proven to be valuable because, when applied in technology and medicine, scientific knowledge is powerful knowledge. Here’s an example. The graph below shows human life expectancy in the different regions of the world from the eighteenth century onwards. Looking at the line showing the world average we see that, on average, a person born in the eighteenth century could expect to live for about 30 years. Just 30 years. It is primarily due to advances in biology, chemistry, epidemiology etc., all of which have transformed technology and medicine, that a baby that was born in 2021 could expect to live more than twice as long, to about 70 years. So life expectancy has more than doubled over the last 200 years! Put simply, it’s difficult not to value science, if you value your life. Of course, scientific advance is responsible for destructive technology, too. But here’s a thought – ‘in spite of the fact that science could produce enormous horror in the world, it is of value because it can produce something’ (Feynman, [1955], 1999).

Beyond giving us power and a better understanding, there is third way in which science is valuable that has remained rather unappreciated in the public mind. To explain what it is, I will take you on a journey back to Victorian Britain.

A Victorian craze

The 1850s was a spectacular decade for science that brought us the theory of thermodynamics, pasteurisation and the theory of evolution through natural selection, among other things. But the 1850s was also a decade in which a strange ritual called ‘table-turning’ spread like a shockwave through the world, including the UK. It involved a group of people who gathered round a table with a medium who was there to facilitate communication with the dead. The group would place their hands on the table and then, as they gently raised their fingers, the table would lift itself off the ground accompanied by tapping noises that signalled a response from beyond the grave. Nobody was quite sure how table-turning worked but many believed that it is for real. Many, but not all.

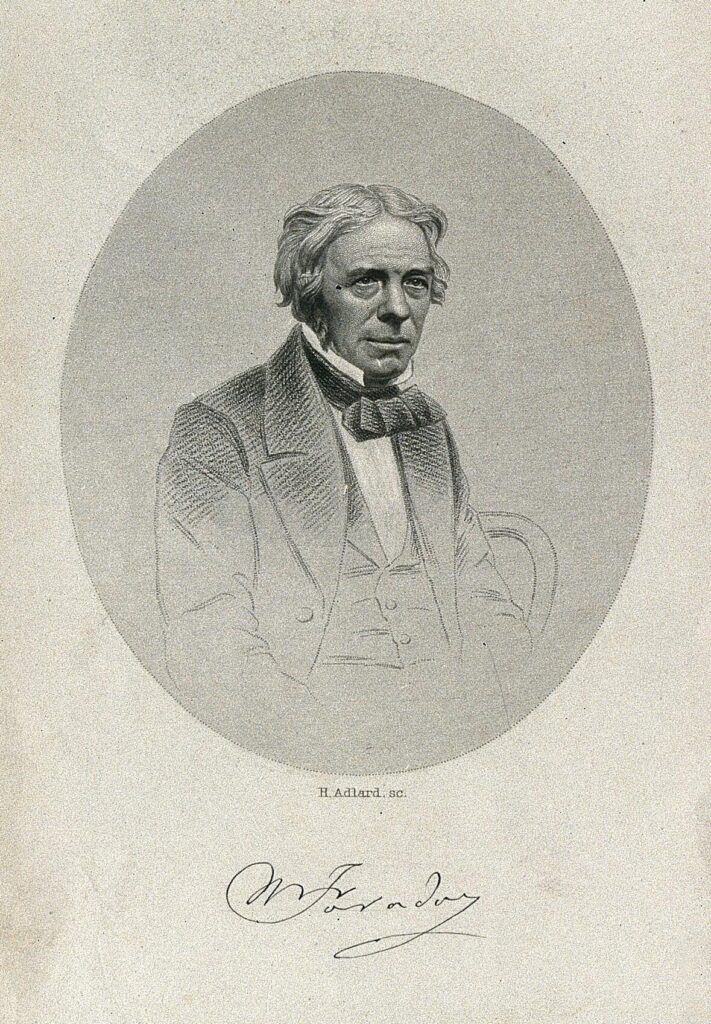

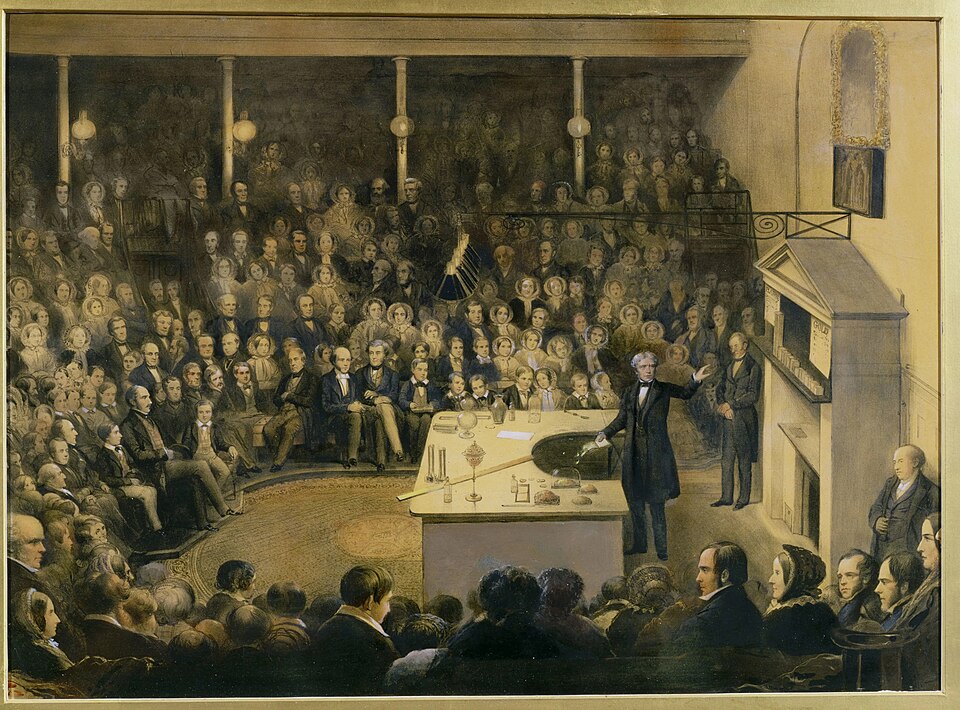

One of those who were highly sceptical was Michael Faraday (1791-1867), Professor at the Royal Institution and one of the most well-known and respected scientists of the day – he first showed that electricity can be generated by moving a magnet within a coil of wire. According to Faraday, suspicion of table-turning was well justified, since it contradicted almost all of contemporary physical knowledge, the law of gravity, for one thing. Being well-known, Faraday received so many letters from the public asking for his expert view on the matter, that he eventually agreed to put table-turning to an experimental test.

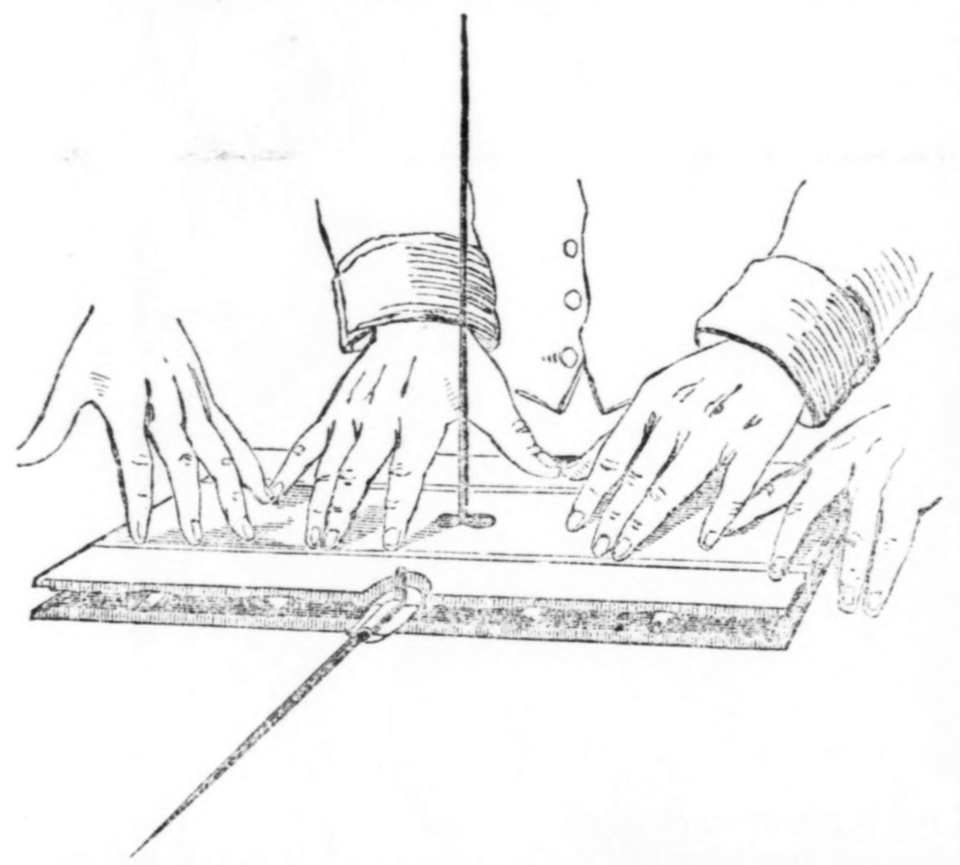

To cut a long-story short, Faraday undertook a series of experiments during table-turning seances and was able to show that the so-called self-turning of tables was merely the result of ‘the unconscious motions of the hands upon the table’ (Faraday, 1854). He explained his approach and results in a letter to the editor of The Times and displayed his apparatus for everyone to see in a London shop. Table-turning was debunked. But that wasn’t the end of the story, at least not as far as Faraday was concerned.

Source: Illustrated London News, 16 July 1853, p. 26.

A deeper problem

What shocked Faraday, and shocked him much more deeply than table-turning itself, was how easy it had been for a great majority of people to unquestioningly accept such a fantastical idea as table-turning that contradicted all of contemporary physics. In an age of scientific advance, why were people so easily and completely won over by ‘self-lifting’ tables that brought news from the ‘other world’?

‘I think’, Faraday wrote in his letter to the Times, ‘that the system of education that could leave the mental condition of the public body in the state in which this subject has found it must have been greatly deficient in some very important principle’.

In a follow-up lecture the following year, Faraday argued that it wasn’t supernatural fads that plagued British society but a ‘deficiency of judgment’ (Faraday, 1854). He also argued that a proper scientific education for all might help to address this want.

Scientific values

But what did Faraday mean by a proper scientificeducation? What he meant was educating children, or the general public, not merely about facts – what scientists discover or invent – but also about the procedures that enable scientists to make discoveries; he meant teaching people the mental disciplinewhich scientists learn to adopt and which, Faraday thought, anyone can learn and adopt; he meant a scientific education that helped people develop a scientific worldview and embrace the scientific values which underpin that worldview. But what is a scientific worldview? What are scientific values?

Scientific values are values of the scientific community which scientists learn to adopt as part of their training and which guide their approach and their work. Let’s look at four examples.

Scientific values I – Respecting empirical evidence

All scientific work begins with a set of conjectures, usually conflicting conjectures, about how something in nature works. What happens next is interesting – scientists design experiments that enable them to put these conjectures to an empirical test. The whole point of doing an experiment is to enable scientists to distinguish between more and less accurate conjectures. This in turn means that one must be prepared to abandon a conjecture if it turns out that it does not correspond to empirical reality.

So, in science, respect for empirical evidence entails a commitment to test ideas empirically and to abandon ideas for which there is little empirical justification. It entails preparedness to change one’s mind.

Of course, scientists are humans, too and like everyone else they often find it difficult to change their mind about an idea, especially if it is their own idea. But while it might be difficult for individual scientists to always follow this commitment, what matters and has made all the difference in the last four hundred or so years is that the scientific community as a whole strives to follow it.

Scientific values II – Taking a strict approach to uncertainty

Next in the line-up of scientific values is the commitment to adopt a very strict approach to uncertainty. In 1854, Faraday put it this way: ‘except where certainty exists (a case of rare occurrence), ‘we should consider our decisions as probable only’ (Faraday, 1854).

A century later, the physicist Richard Feynman described it this way: ‘When a scientist does not know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty darn sure what result is going to be, he is in some doubt’ (Feynman, [1955], 1999).

Faraday and Feynman were talking about the same approach but while in Faraday’s time, the scientific approach to uncertainty was a matter of mental discipline; by the time of Feynman, advancements in statistics had made possible the precise estimation of the uncertainty associated with scientific hypotheses.

Adopting a scientific approach to uncertainty is not the same as being sceptical. Scepticism doubts the possibility of knowledge, whereas a scientist leaves room for doubt precisely because he or she is positive that a better understanding is possible. Also, the scientific approach to uncertainty is not doubting for doubting’s sake – it carries the commitment to show the basis of one’s doubt, to propose alternative solution and work out the consequences.

Scientific values III – Taking responsibility for one’s claims

This last point takes me to my third example of a fundamental scientific value – the commitment to take responsibility for one’s claims. When investigating table-turning, Faraday was adamant that it was the responsibility of those who believed in table-turning ‘to work out the experimental proof’ (Faraday, 1854). ‘Why should not one who can thus lift a table, Faraday asked, proceed to verify and simplify his fact, and bring it into relation with the law of Newton?’ (Faraday, 1854). To overturn even one of Newton’s laws would be to destroy the very foundation of modern physics as it stood in Faraday’s time and it was obvious to Faraday that those prepared to accept the ‘reality’ of table-turning were not fully addressing the consequences of their acceptance.

Scientific values IV – Fighting bias

Honouring the three commitments I mentioned is difficult, not least because all humans, including scientists, suffer from biases. When discussing table-turning, Faraday observed that: ‘In place of practising wholesome self-abnegation, we ever make the wish the father to the thought: we receive as friendly that which agrees with [us], we resist with dislike that which opposes us […]’ (Faraday, 1854). This all too human tendency is well-known today as confirmation bias. Scientists are no more immune to biases than the rest of us but the scientific community as a whole adopts procedures that enable it to reduce bias in their collective judgment on scientific matters, procedures like randomisation, double-blinded trials, strict standards for scientific reporting and so on.

Scientific values and the value of science

Why are scientific values important? In one of his books, the scientist and science populariser Jacob Bronowski (1907-1974) argued that scientific values, ‘derive neither from the virtues of its members, nor from the finger-wagging codes of conduct by which every profession reminds itself to be good. They have grown out of the practice of science, because they are the inescapable conditions for its practice’ (Bronowski, 1956). In other words, Bronowski is saying, scientists couldn’t have achieved what they have achieved in the last four hundred years by following a different set of values.

So, scientific values are important because they have been crucial for the cognitive progress of science. But, as we have seen Faraday and others have claimed a lot more for these values – they have claimed that these values, when part of wholesome scientific education, contribute to the social value of science.

And this takes me to the central proposition of this post – the argument that science is socially valuable not only for its fundamental insights into the workings of the natural world or for its pivotal role in technological development, but because a scientific education (done properly) can instil in anyone respect for scientific values. Adopting these values in turn can nurture good mental habits which can help anyone cultivate a precise, careful and unprejudiced judgment, as far as this is possible, on any subject.

Science as education

As we have seen, scientists have emphasised that scientific values are human values, so, in principle at least, we must all be capable of learning how to adopt them. In the same way in which these values help scientists navigate the complexities of scientific research, if adopted more widely, scientific values can help the ordinary person navigate the complexities of daily life. However, what is easily said might not be so easily done. If following this set of values we discussed works so well in science…and if scientific values are universal human values…and if they can help us navigate the complexities of daily life…then why has it proven so difficult to ‘import’ them into our everyday way of thinking?

Some might even argue that adopting ‘scientific values’ in everyday life is not even practical (certainly not in any way more practical than attempting to extract the stone of folly from a person’s head, as the surgeon in the sixteenth-century painting below is attempting to do!).

Why is that? Is this scepticism justified? Firstly, as I already mentioned, scientific values are the values of the scientific community, not of individual scientists. We have evidence they work at community level, but what evidence do we have that the individual scientist, finds it easy to apply those same values outside of his/her work, in situations where they are not compelled to do so by the scientific protocol? What do you think? To what extent can you in your daily life honour the commitments which the adoption of scientific values entails?

Here’s another vexing issue. Taken at face value, the scientific way of thinking that scientists have urged us to adopt in everyday life does not appear in any way to violate good common sense. The question is, however, to what extent is it indeed possible that ‘thinking scientifically’ becomes ‘second’ nature? Given that life doesn’t happen in a lab, can scientific values apply just as well in dealing with the complexities, controversies and contradictions of everyday life?

And then, another vexing issue – the place of science in culture. The values people generally adopt are the values of their culture. But there is a strong argument to be made that science is not really part of culture as we understand it. As Jacob Bronowski cleverly pointed out, culture, at least as far as Europe is concerned, ‘is Sophocles and Chaucer and Michelangelo and Mozart and the other figures round the base of the Albert Memorial’ (Bronowski, 1956). Culture is music, poetry, sculpture, paintings…Is there a place for science in culture, and if yes, what is it?

‘Man is not […] a perfect being, but perfectible’ (William Godwin, 1793).

Whether scientific values should be widely adopted, or not, is clearly open to debate. As we’ve seen, those who think they should be adopted, think they should be adopted through education and by appealing to rational argument. But as we’ve also seen, this has proven rather difficult. However, to dismiss the idea that these values can be widely adopted through education would be to give up the ideas of education and rationality, ideas which sit at core of the Enlightenment vision of progress and the perfectability of human beings. We might never be ‘perfect’ – ‘perfectly’ rational, ‘perfectly’ balanced, ‘perfectly’ unbiased, ‘perfectly’ ‘scientific’. But, as the wife of the great Scottish engineer James Watt once told their son Gregory – ‘We live but to improve’ (Annie Watt quoted in Porter, p. 424). If all else fails, we can always go back to the 17th century’s tried and tested method:

A surgery where all fantasy and follies are purged and good qualities are prescribed!

References

Jacob Bronowski, Science and Human Values (New York: Harper and Row, 1956).

William Godwin, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness (London: Printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, Paternoster Row, vol. 1, 1793, p.118).

Michael Faraday et al., Lectures on Education delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain (London: John W. Parker, 1854).

Richard Feynman, The Pleasure of Finding Things Out (Cambridge Mass.: Perseus Books, [1955], 1999).

Roy Porter, The Creation of the Modern World: the Untold Story of the British Enlightenment (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Co., 2000).

Further reading

T. H. Huxley, Science and Education(London: Macmillan, 1895).

Jim al-Khalili, The Joy of Science (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022).

Vaclav Smil, How the World Really Works (London: Penguin, 2022).

Lewis Wolpert, The Unnatural Nature of Science (London: Faber and Faber, 1992).