In May 2025, I took part in a panel discussion entitled We Need to Talk about History at the Public Communication of Science and Technology (PCST) conference in Aberdeen. The panel members were Professor Bruce Lewenstein, Dr Felicity Mellor, Professor Agustí Nieto-Galan and myself. What brought us together was a common interest in the history of science popularisation and a conviction that to do their job more effectively science communicators would benefit from even a basic grounding in the history of science in general and their own field in particular. Each of us in the panel used examples from different periods in the history of science communication to launch a discussion about the challenges, the tensions and the growing problems that science communicators face.

For my part, I focussed on the challenges in establishing and maintaining trust between science communicators and their audiences. More specifically, I looked at the activities of two prominent eighteenth-century science communicators to reflect on 1) what forms the basis of public trust in science and 2) some of the challenges that communicators face in earning the public’s trust. Below is a summary of these reflections.

. . .

London, 1738. In the City of Westminster, in a small street called Channel Row stands a house that frequently draws visitors from the British elite and scholarly circles.

One visitor described the house as:

[…] the strangest looking place I ever beheld & appears very much like the abode of a Wizard. The Company that frequents it is equally singular consisting chiefly of a set of queer looking people called Philosophers. […] ’Tis well if among all these Conjurors I do not turn witch.[1]

The description comes from a letter that the poet, scholar and translator Elizabeth Carter (1717-1806), wrote to a friend, Mrs Underdown. So, whose house was this?

It was the house of John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744) – a natural philosopher, engineer and one of the best known and respected communicators of experimental and natural philosophy in the early eighteenth century. At the time of writing, Carter had visited Desaguliers’ home in Channel Row several times. This was also the house in which Desaguliers delivered his public lectures between 1715 and 1739.[2]

It is clear from the amusing tone of the letter that Carter didn’t seriously believe that Desaguliers was a ‘Wizard’. In fact, in a poem she published the same month in The Gentleman’s Magazine she celebrated Desaguliers’ ‘happy talents’ – evidence that she trusted and respected him as a philosopher and educator:

[…] Science turns pride, and wit’s a common foe,

But where good nature to these gifts is join’d,

They claim the praise and wonder of mankind:

All view the happy talentswith delight,

That form a Desaguliers and a Wright.[3]

Carter’s reference to ‘Conjurors’ in a private letter is nonetheless revealing because it implies that even somebody like her who committed time, money and effort to learn science, still found it a daunting activity and struggled perhaps to fully grasp the processes involved. To this day when we don’t fully understand an activity, we have a natural tendency to compare it to magic. These two excerpts from Carter’s writing – the private letter and the published poem – invite the question: How much of her trust in Desaguliers came from a proper understanding and how much – rested on her perception of his authority? And more broadly: Given the complex nature of science, can lay audiences ever avoid relying on their own perceptions of communicators’ authority and credentials when deciding whom to trust?

The Carter-Desaguliers episode is only one of many episodes from the eighteenth-century history of science communication that offer an opportunity to investigate what constitutes the basis of public trust in science. Whether that trust ends up resting on a proper understanding or merely on a perception of the authority of scientists and communicators depends, among other things, on the extent to which communicators put emphasis on education as opposed to, say, entertainment and hype. Balancing the educational and entertainment elements in science communication has always been a difficult challenge. Even nowadays, with better educated populations and communicators having more sophisticated tools that can reach wider audiences, the challenge remains and, consequently, the implications for public trust are as great as ever.

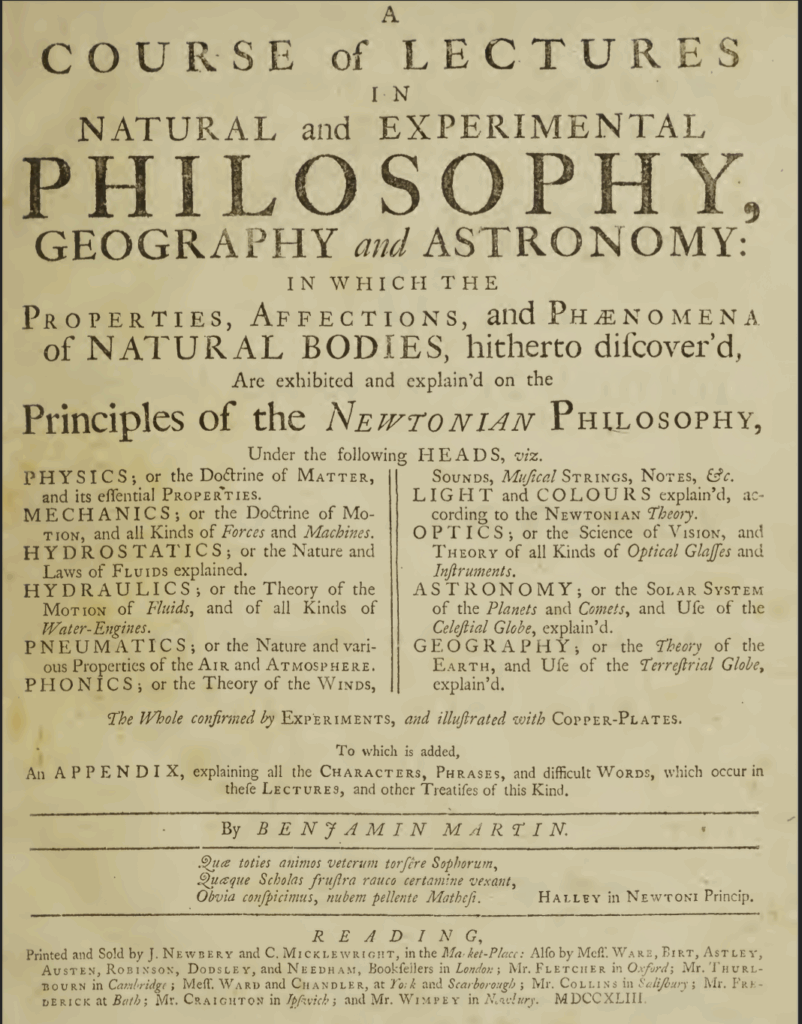

Studying the work of eighteenth-century science communicators also provides material for exploring the challenges of earning the public’s trust. Consider the case of Benjamin Martin (1704–1782)– a successful itinerant science lecturer, a well-known instrument maker and a prolific writer.

In the Preface to his Course of Lectures on Natural and Experimental Philosophy (1743), Martin wrote:

[…] Knowledge is now become a fashionable Thing, and Philosophy is the Science a la mode.[4]

However, he was particularly concerned that:

[…] there are many ignorant and empirical Pretenders gone out, who obtrude themselves and a spurious Apparatus on the good-natur’d and generous Part of Mankind, who are not apt to suspect or think ill of a Person, till (too late they find) they have been decoy’d and deceiv’d by him; and then they are prejudiced against and reject all Proposals of this Kind for ever after.[5]

So, according to Martin, his own efforts to earn and maintain public trust were being undermined by impostors who were spreading false ideas about science. If we are to believe his own account, the consequences for him were serious:

And to say the Truth, there are many Places […] that they have taken me for a Magician; yea, some have threaten’d my Life, for raising Storms and Hurricanes: Nor could I shew my Face in some Towns, but in Company with the Clergy or Gentry […].[6]

It is clear from this example that earning the public’s trust successfully depended not only on the communicator’s own efforts and reputation, but also on who else was occupying the public stage. The challenges Martin faced remain with us today, and have perhaps become even more difficult to address since ‘the public stage’ has grown so much that it’s hard for science communicators to even know who else is out there and what ideas – true or false – they are popularising.

[1] Elizabeth Carter to Mrs Underdown, 23rd June 1738. In Hampshire, G. Elizabeth Carter, 1717-1806: an Edition of Some Unpublished Letters (Newark, University of Delaware Press, 2005), pp. 43-44. Carter was a highly educated woman. She learnt nine languages (Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic and German) and is best known for the first English translation of the works of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. She was also a member Blue Stockings society. In the history of science popularisation Carter is best known for the first English translation of Francesco Algarotti’s Neutonianismo per le Dame (1737) which was published in 1739 in London as Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophy Explain’d for the Use of the Ladies.

[2] For more details about Desaguliers’ lecturing in London and beyond, see Chapter 2 in Carpenter, A. T. John Theophilus Desaguliers: a natural philosopher, engineer and freemason in Newtonian England (London, New York: Continuum International Pub. Group, 2011).

[3] Carter, E. ‘While clear the night, and ev’ry thought serene’. Gentleman’s Magazine (London: Printed by E. Cave, June 1738, p. 316). The ‘Wright’ in the poem is the astronomer Thomas Wright (1711-1786) who was a friend of Carter and who taught her astronomy, maths, Greek history and geography. It was Wright who took Carter to Desaguliers’ house in 1738.

[4] Martin, B. A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy, Geography and Astronomy (Reading, 1743), Preface.

[5] Martin, B. A Course of Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy, Geography and Astronomy (Reading, 1743), Preface.

[6] Martin, B. Supplement Containing Remarks on a Rhapsody of Adventures of a Modern Knight-Errant in Philosophy (Bath, 1746), pp. 28-9.

Great post!

Thank you!